Angel With a Wandering Eye

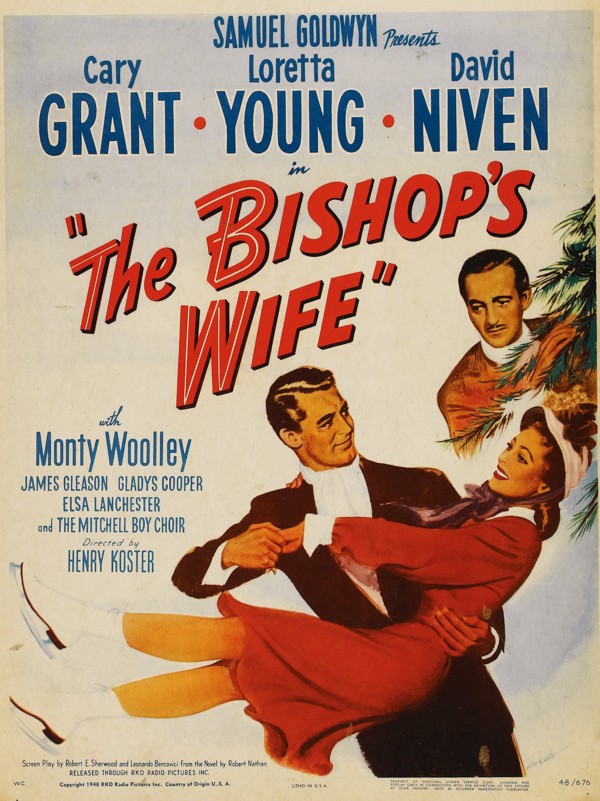

Cary Grant stars as Dudley. Of course, since he is personified on screen by Cary Grant, Dudley is a charming, good-natured fellow; but Dudley is no ordinary man. In fact, he is not a man at all: he is an angel. All in the line of divine duty, Dudley brings smiles to people's faces as well as direction and enlightenment to people's lives; though most are oblivious to his holy foundations. When Bishop Henry Brougham (David Niven) prays for guidance amidst a time-consuming and stressful effort to build a new cathedral in a wealthy part of town, straining his relationship with his wife Julia (Loretta Young), Dudley is assigned to help facilitate the Bishop in both his professional and personal life. But as much as Dudley helps, he also impedes when he begins to fall for Julia.

Production on The Bishop's Wife was far from heavenly. Producer Samuel Goldwyn was dissatisfied with what original director William A. Seiter (director of many classic comedies, including installments of legendary Marx Brothers, Laurel & Hardy and Shirley Temple films) had shot, replacing him with Henry Koster (Harvey (1950)). Even this change at director did not equate smooth-sailing for the film, feedback from test audiences was less than perfect so Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett were hired for some final uncredited rewrites. The many personnel changes did not negatively affect the film however, The Bishop's Wife is very well assembled. Gregg Toland (The Grapes of Wrath (1940), Citizen Kane (1941)) does an incredible job photographing the film and replacement director Henry Koster received an Academy Award nomination for his work.

Although the story generally makes me stop and pause, as the idea of an angel falling for another man's wife at the very least strays into unhallowed territory, The Bishop's Wife contains a lot of spirit and value. Dudley helps the Bishop to see that he not only needs to pay more attention to his family but he must also gain perspective on where his ministry is focused. Sometimes what is big, bold, beautiful and well-intended does not meet the spiritual needs of the many. Of course the story has plenty of room for great comedy, of which the cast and filmmakers did not waste! The many different thematic and comedic elements of the film make The Bishop's Wife a very fun and warm experience. The cast helps this too. Film legends Cary Grant, David Niven, Loretta Young and Elsa Lanchester are absolutely excellent in their roles; Grant's strong presence but humble comedy, Niven's sniveling but sympathetic demeanor, Young's angelic grace and Lanchester's quirky energy really brings the characters and story to life in a fun, engaging way.

Christmas means more than lights, snow, presents or any other material thing but sometimes the right films go far in completing the joy of the season. The Bishop's Wife is one of the better Christmas films around; its wonderful characters, comedy and thematic value make it a seasonal must-see.

CBC Rating: 8/10

.jpg)